Jack Kerouac and Ayatollah Khomeini walk into a bar…

Okay, not really. To our knowledge, there’s no joke featuring this unlikely pair. However, they do appear in the same story. These two notable figures play opposing bookends in a short but magical era of hippie folklore: The Hippie Hash Trail.

Kerouac inspired its beginning. The Ayatollah brought it to an end.

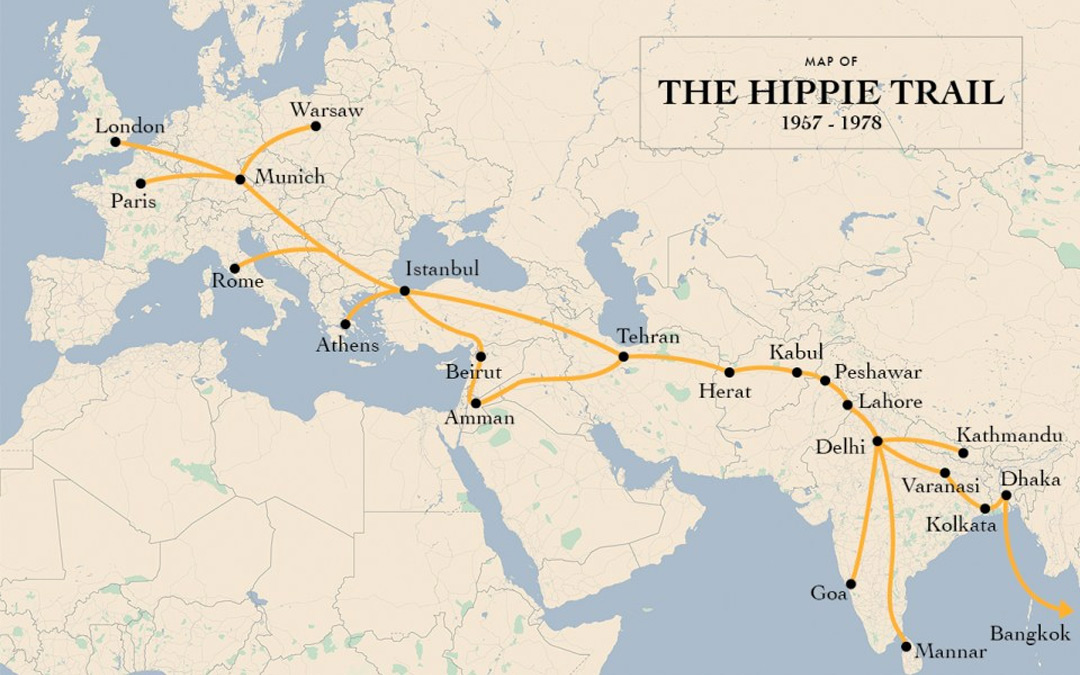

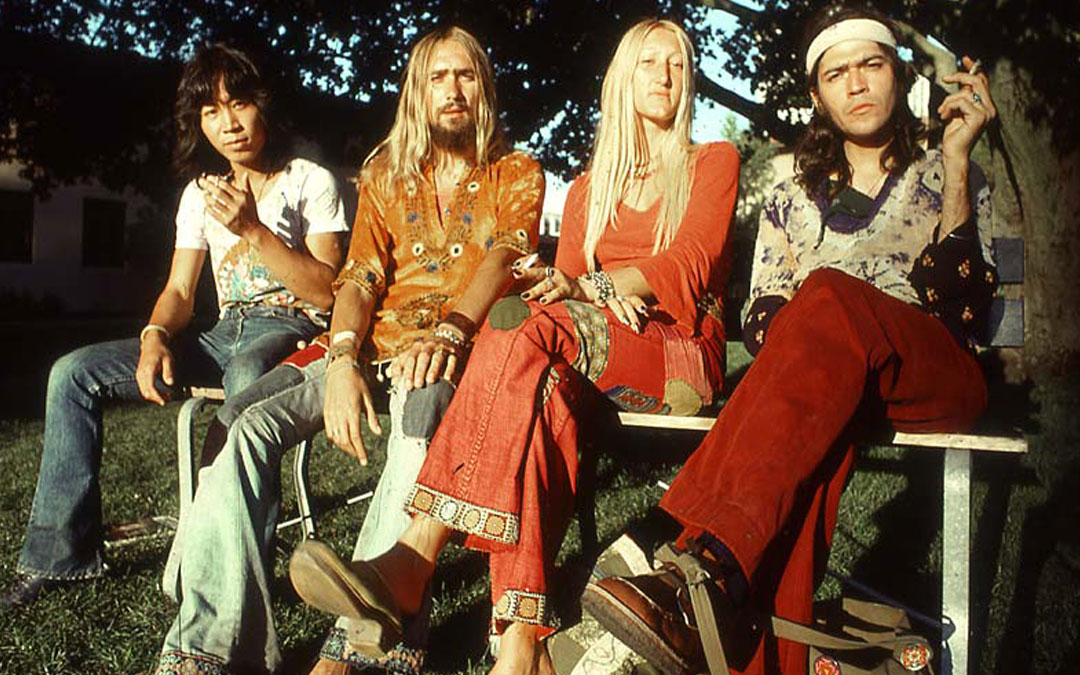

The Hippie Trail was an overland path from Turkey through Afghanistan into Nepal and China – a pilgrimage to the world’s best producers of hashish. Beginning in the late 1950s and continuing through the late 1970s, the trek became a rite of passage for disaffected young idealists who called themselves “Beatniks”, then rebranded themselves as “Hippies” in the 1960s. They left comfort, family, and jobs behind, booked a flight overseas, and embarked on a quest to discover… well… most weren’t quite sure what awaited them. They were kids, they wanted adventure, they wanted freedom, they wanted to get blazed.

Many came away with great memories and experiences. Others saw their dreams of utopia turn to disillusionment. A few never made it back.

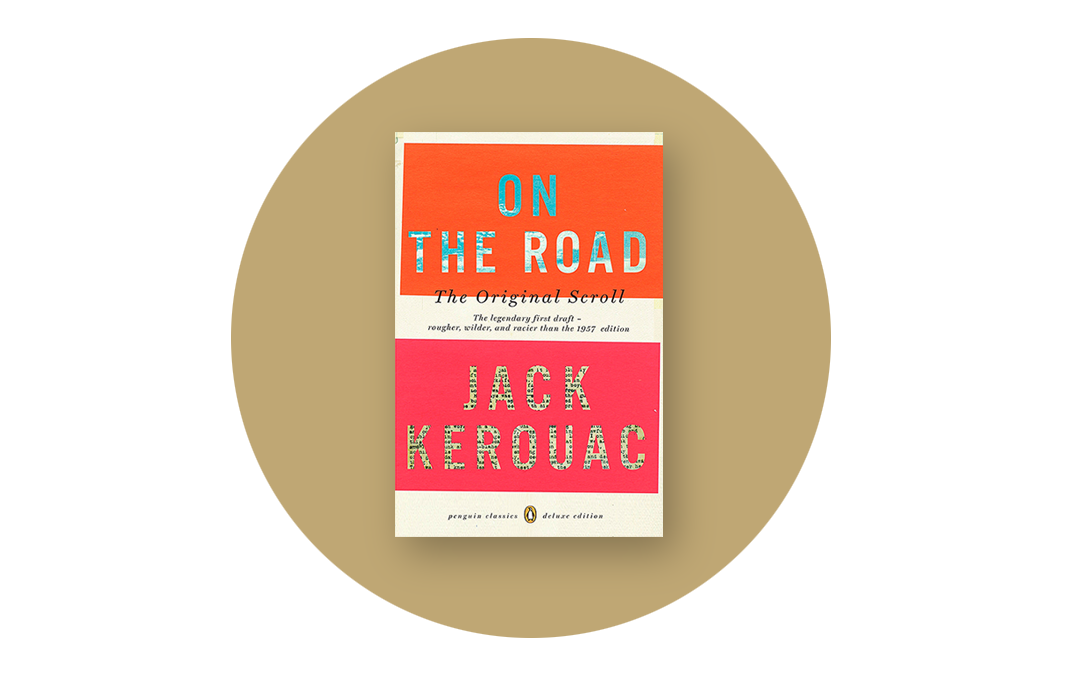

Hit the road, Jack

Jack Kerouac’s On The Road was published in 1957. Its idealized account of life on the road caught the imagination of the younger generation, triggering a hunger for a simpler, freer life than the one their parents were leading. Teens decided they didn’t need the pressure of starchy Western conservatism. Many rebelled by growing their hair, putting on jeans, and listening to Elvis. A few took it further… by a few thousand miles.

Eastern culture had always held an attraction to the Beatnik movement, but the foreign lands and cultures were as far removed from their lives – and as practical a destination – as the Moon. It took a few notable celebrities and a bus company to turn the vast unknown East into a tourist destination for restless youth.

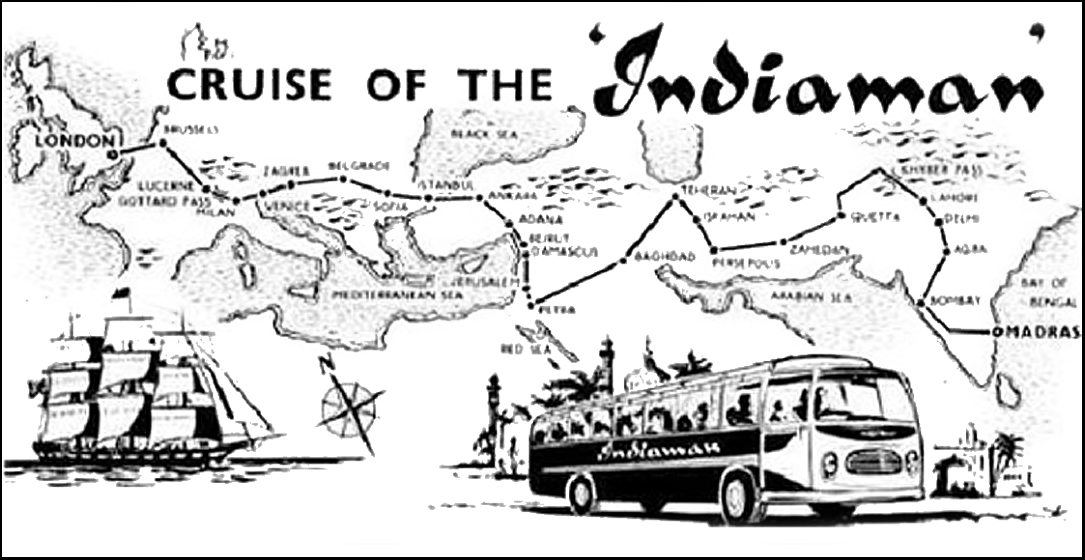

The actual route they were planning to take had a famous history. The overland path from Asia to Europe was trudged 400 years earlier with the Silk Road, the historic trade route that introduced Eastern goods (including hashish) to the West. Centuries later in the 1950s, the path was used by British scientific expeditions, who crossed the terrain in rented buses.

In 1957, the Indiaman Bus Company had the idea to market the route to the public, rebranding it as a trip into the ‘Mystic East’ – the original magical mystery tour. A trickle of Western ‘intrepids’ took notice. So did competing bus operators, who quickly jumped on the commercial bandwagon. Tour buses in London and Istanbul began advertising trips across the rugged terrain of Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, and Nepal, painting an exotic picture of communal living, spiritual enlightenment, and the best hashish on the planet – straight from its birthplace.

Marketing of the East was boosted further when it was embraced by iconic figures of the time. In the early-60s, Alan Ginsburg moved to Varanasi, India. A few years later, The Beatles found their spiritual centre in an Indian ashram. In 1969 Jimi Hendrix found sanctuary in the Moroccan town of Essaouira. Eastern culture was becoming decidedly fashionable, not to mention Western-friendly.

Happy trails

As Eastern mystique grew, so did the buzz surrounding the Hippie Trail. An excited stream of hash trailblazers began booking cheap flights and stuffing their backpacks. Americans, Europeans and Aussies began arriving, starting their Hippie Trail journey from different cities. The influx of travellers began spawning a self-contained tourism industry, with Western youth looking for ways to communicate and share experiences. Travel guides started appearing, first as roughly typed, hand-stapled giveaways, then as commercially published booklets. In them, hippies could find tips on where to live and eat along the Hippie Trail. The advice was written by and for hippies:

“In Afghanistan in particular you can get stoned just by taking a deep breath in the streets,” One guide listed the best places to “socialize, pick up rides, chicks, guys, etc.”

The famous travel guide, Lonely Planet, published its very first booklet, Across Asia on the Cheap, as a collection of practical tips for fellow Hippie Trail travellers.

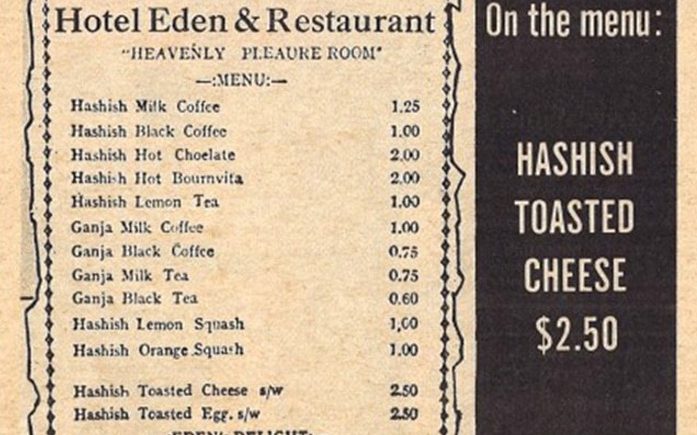

Buses advertised overland trips that would take you from Europe to Nepal in just four weeks. Cafes and shops across the Middle East changed their menus and added english writing to attract the hippie travellers.

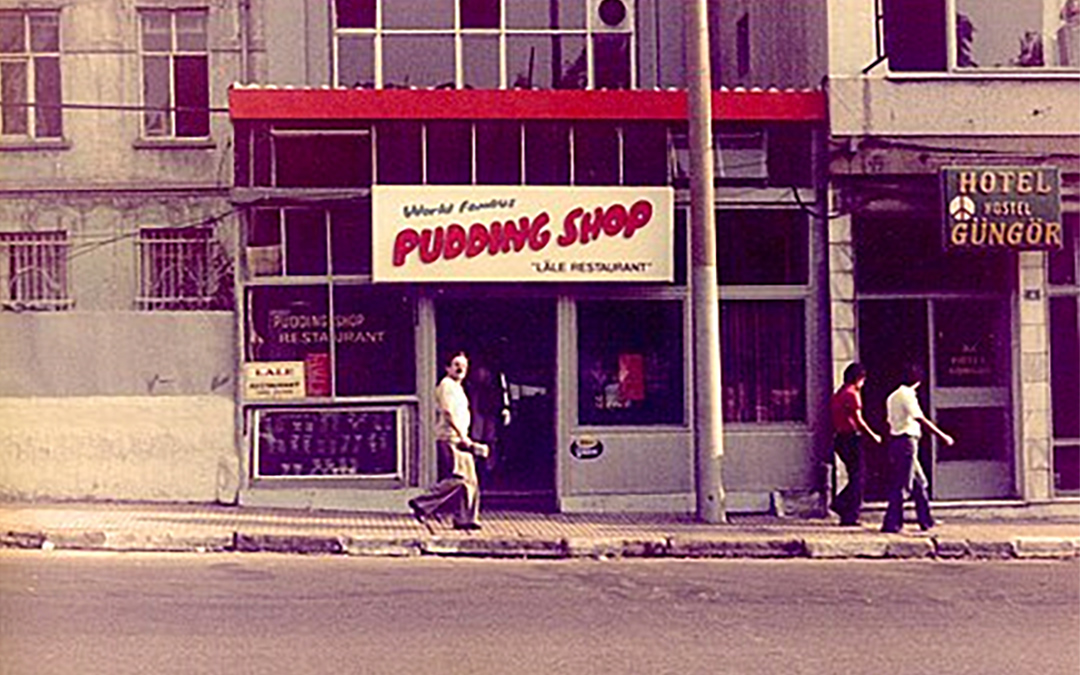

The Pudding Shop was the name given to a small restaurant in Istanbul that became a hub for Western travellers. Its real name was the Lale Restaurant – people started calling it ‘the pudding shop’ because of its selection of puddings. The owners were thrilled to get free publicity and changed the outdoor sign to capitalize on the popularity. They also added a bulletin board inside, where travellers could leave notes and personal messages for each other, as well as travel tips for the next planeload of travellers – a pre-internet message board.

Another famous Hippie Trail attraction was Freak Street, a small street in Kathmandu that became wildly popular among travellers for its strip of government-run hashish shops. The variety of legal substances made it a must-visit location on the journey.

Each wave of travelling hippies passed information onto the next wave, accumulating a list of the best guesthouses, friendliest hosts, cheapest breakfasts, and where to score the best quality hashish. By the 1970s, the Hippie Trail was no longer unknown or mysterious. Its well-mapped routes had turned it into a theme park for Westerners looking to get away, get laid, and get baked.

No destination

A decade of kids had been travelling east, following the same paths and visiting the same hotspots. By the mid-70s the mysterious East had become far less mysterious. The only thing left to discover about the Hippie Trail was whether it was worth going. Thousands of hippies had travelled thousands of miles to spend months in faraway lands, with little idea of their final destination and no clue what to do once they got there. If you simply wanted to escape or were looking for adventure, you probably came away satisfied. There was no shortage of experiences, fellow travellers, drugs and sex.

However, those on a quest for deeper truths began to realize that no matter how far they went or how high they got, there was no carefree new life waiting for them on the other side of the planet. The mountains were spectacular, the ashrams inspirational, the food exotic. But then what? Spiritual connections don’t pay a salary or translate a foreign language. The hippies were ultimately strangers in a strange land.

Indian entrepreneur, Rama Tiwari, who made his fortune during the Hippie Trail era, recognized the fundamental flaw in their expectations: “(The) hippies made one mistake, and it broke them. They imagined peace of mind was not with their families or in their home countries. They didn’t see that we can only live in happiness if we conquer the restless dream that paradise is in a world other than our own.”

Months after arriving, many young hippies found themselves broke and homesick. Sadly, others suffered a crueler fate. In the 1970s, over 20 travellers were murdered by Charles Sobhraj, a French-Indian serial killer who befriended young Western hippies, then robbed and murdered them. His story was told in three non-fiction books, as well as a 1989 made-for-TV film and a Netflix miniseries released this year.

As the decade leaned into its final years, the novelty of the Hippie Trail began to wane, along with its naive utopian dream.

Sundown on the dream

By the late 1970s, the hippie generation had reinvented popular culture worldwide. Their music, clothing, liberal values, relaxed rules – the building blocks of rebellion – were now being embraced by the establishment they were supposed to be rebelling against. Even hash and cannabis were becoming mainstream.

Hippie accessories were selling like hotcakes, but the sun was setting on the hippies themselves.

20 years had passed since Kerouac published On The Road. The first hippies had turned 30, they were starting careers, having babies, paying mortgages. The music that jolted the popular consciousness in the 1960s was now being repackaged as Greatest Hits albums.

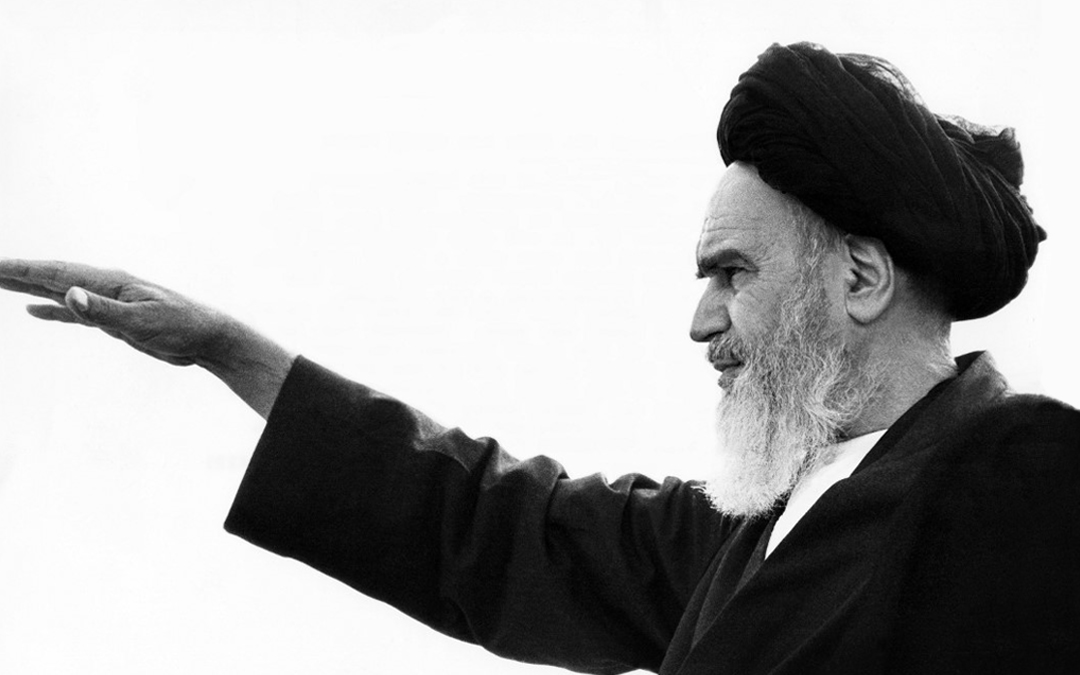

The aging hippies – the first baby boomers – could now afford to fly to Istanbul and travel the Hippie Trail first-class. Unfortunately, they were no longer welcome. The Iranian revolution brought Ayatollah Khomeini to power, who promptly closed the borders to Americans.

Afghanistan was at war, its vast and fertile mountain trails now part of a battlefield. Many Hippie pilgrimage sites were destroyed by the Taliban in 2001.

Hippies had left Kathmandu a mess. Nepal’s police began demanding payoffs to extend their visas. The government banned cannabis products and deported the foreigners to India. Hippies had overstayed their welcome.

The Boomer Trail

Today, the old Hippie Trail is experiencing a slight revival, although it’s now a tourist attraction for Boomers rather than a pilgrimage for rebels. The Pudding Shop is still there, but the bulletin board that was covered with love notes and maps to hash-shops now contains straightforward travel tips.

Kathmandu’s Old Freak Street still exists, with the occasional tourist trying to recapture yesterday’s idealism. However the old scene is gone, replaced by souvenir shops and shopping centres.

Hashish remains illegal in Nepal, Afghanistan and Iran, although officials usually turn a blind eye to locals enjoying some of the world’s best produce. Despite the laws, cannabis plants grow freely on streets and backyards of Afghan cities. In Iran and Nepal, hashish is easily found in clubs, parks and streets, where small-time dealers and enthusiasts will be happy to sell you some.

The far East remains a goldmine for high-quality hashish, however visa restrictions and war have made those countries – and the Hippie Trail itself – difficult to access for Westerners. These days, the safest way for outsiders to experience the historic trail is from 30-thousand feet; the safest way to experience authentic Eastern hash is to order it online.

The intrepid few who insist on recapturing an era can still visit those faraway cities, but the Western idealism of the 1960s packed up and left a long, long time ago. The last remnants of the Hippie Trail are the grey haired tourists snapping selfies.